PAGE 52

The following article appeared in the Jan. and Feb. 2004 issues of "Talkin' Tokens" magazine, monthly magazine of the National Token Collectors Association:

Durfee & Peck

Indian Traders at

Fort Union, Dakota Territory

and

Fort Buford, Dakota Territory

by Jerry Adams

Copyright © 2003

INTRODUCTION

Although Durfee & Peck tokens are not extremely rare, I acquired my first recently at the 2003 NTCA national show in Omaha. Remembering that I had read of the token series in one of my exonumia books, I began to search my exonumia library, for information on them. Finding very little information in my books, I set out to find out for myself the historical setting of the tokens, the place where they were made, and who used them, where and how they were used. This writing is the result of that search, and I hope that it will add to the available written record concerning the background of Durfee & Peck, Indian traders.

Fuld implies on page 208 of Token Collector Pages, that the Durfee & Peck tokens may have been used at Forts Union and Fort Buford. This was my starting point for research. I set out to verify where D&P had trading posts that might have used tokens (human fallibilities have surely made my list too short). I did verify that D&P had trading posts at both Ft. Union, D.T. and at Ft. Buford, D.T. I have been unable to verify Fuld's implication that the tokens were used at those two locations. I suspect that the tokens were used at many of their trading posts. In fact, I suspect D&P intentionally ordered tokens without a location stated on them, in order to be able to use them at many trading posts. The best proof would be the discovery of one of the tokens "in situ" at an archeological dig near one of the forts.

Fur trading posts in 1868 were inherently transitory, and a single outpost might last 12 months or less. Since Fuld never states that the tokens were used at Forts Union and Buford, but hints at this, I gave that idea free rein and have examined those two posts in detail. Ft. Union, D.T. was a privately built and run fur trading post, not a military post. However, Fort Buford, D.T. was built and run, as a military post of the U.S. Army.

VIGNETTE

The year is 1867, the place is the civilian trading post named Fort Union, Dakota Territory. A matte of muted green native grasses stands knee high along river's banks. On the first terrace above the water can be seen a few Indian teepees and small campfires, seemingly randomly spaced from near the river's edge to past the log fortifications. Through the smoky haze of this early April morning, a sidewheel steamship churns westward against the current. The vessel stays in the center channel of the Missouri River and sounds its whistle.... just as the American flags of the fort are visible. The steamship whistle speaks again: WHOOOOOO!! WHOOOOO!!! Muffled baritone voices can be heard across the water, then suddenly....

BOOM!!! ...the fort's cannon fire a welcoming salute! As the steamship's engines reduce power, clouds of smoke rise from the steamer's twin stacks, and the vessel carefully steers between the sand bars toward the Missouri's shore.

the tokens:

GOOD FOR / 25 CENTS / IN / MERCHANDISE / DURFEE & PECK

(BUFFALO CHARGING TO LEFT)

copper-round-20 mm diameter (circa: 1867-1869, used at Ft. Union, D.T. and Ft. Buford, D.T., estimated value $250 -$400) (also listed in these metals: brass, copper-nickel and white metal) (Curto # 51 ½ in copper, #51 in copper-nickel, and 52V is copper with thick planchet) (Durfee was 39 years of age in 1867, Peck was 36 in 1867)

GOOD FOR / 50 CENTS / IN MERCHANDISE / DURFEE & PECK

(SIDE WHEEL PACKET BOAT)

copper-round-24 mm diameter (Wright # 273, Curto # 48 ½)

GOOD FOR / ONE DOLLAR / IN MERCHANDISE / DURFEE & PECK

(INDIAN WITH SPEAR ON PONY GALLOPING TO RIGHT)

copper-round-27.6 mm diameter (Curto # 47 ¼, brass is Curto # 47 ½, copper-nickel is Curto # 47 ¾

)EARLY FUR TRADE AND INDIAN TRADE IN NORTH AMERICA

The Hudson's Bay Company had been the earliest fur traders of note in the great lakes area. Some even joked that the letters HBC meant "Here before God"! The U.S. Government became involved in the Indian trade in the late 1700's, and from 1796 until 1822 the federal government operated a "factory system", which was a series of trading posts that were government supported, somewhat modeled after HBC. The federal employees that ran these were called "factors" and thus the name factories. These factories stocked Indian goods, and engaged in direct trade with the Indian tribes for pelts, and furs, in the hopes that this would ingratiate the tribes to the federal government. In 1803 Thomas Jefferson proposed a new direction for the factories, which they might extend enough credit to the Indians that they might create massive debts, and thus their only means of undoing the debt with their limited means would be to cede land to the government. The factory system as it existed was pretty much a monopoly, effectively eliminating private trading with the Indians. Also, the law makers of the United States prior to 1865, saw no difference between the fur trade, and Indian trade, they were one and the same virtually and legally.

In 1822, revisions were made to the existing Indian-fur trading laws. The Indian Office was allowed to issue licenses to tide west of the Mississippi for up to 7 years rather than the earlier 2 year limit. Maximum trading bonds were raised from one thousand to five thousand dollars. Also the special superintendent of Indian Affairs would be required to reside in St. Louis, in recognition of that cities large role in the Indian-fur trading business.

In June of 1834, Congress created the Department of Indian Affairs. This new Department had offices in Washington and sent Indian agents and subagents into the field to live with, or near the tribes under their jurisdiction. The president appointed these agents to 4 year terms with the consent of Congress. Regulatory laws dictated that Indian traders file bonds of several thousand dollars before being licensed. Licenses set specific locations for trading posts, and the traders were forbidden from traveling around the countryside looking for customers.

BRIEF HISTORY OF FUR TRADING IN UPPER MISSOURI AREAHudson's Bay Company (HBC) was chartered in 1670 by British monarch Charles II (ruled 1660-1685). HBC merged with the North West Company (NWC) (founded 1784) in 1821, creating the largest fur trading business in area. As with many mergers, many lost their jobs after the merger, three men who lost jobs, Kenneth McKenzie, William Laidlaw and Daniel Lamont, joined Joseph Renville, James Kipp and Robert Dickson to form a new trading company, dubbed "Columbia Fur Company" in 1821, whose goal was to operate mainly south of the Canadian border. Columbia Fur Company (CFC) faced tough competition not only from HBC, but also from John Jacob Astor's "American Fur Company" (AFC), which had opened its St. Louis office in 1822. CFC built four posts in the Minnesota valley, more posts at Lake Traverse, several along the Missouri River, and at Green Bay on the western shore of Lake Michigan. By 1827, Astor's American Fur Co. could no longer stand by and allow McKenzie's CFC to cut into the limited resources. So in July of 1827, Astor's AFC bought out the Columbian Fur Company, keeping the principals, and renaming it the western branch, or "The Upper Missouri Outfit" (UMO), which would be the group that would build Fort Union, D.T. some 18 months later. The chief executive of the newly formed UMO was Pierre Chouteau, Jr., a man of great organizational abilities, descended from one of St. Louis's founding French families. (Those of you who collect Indian Peace medals may recognize the name Pierre Chouteau, as there are privately minted Indian peace medals dated 1843, which his company produced and presented to Indian chiefs. There are also fake Chouteau medals being sold recently on eBay.)

Forts Union and Buford were both located on the upper Missouri River, on the path that Lewis and Clark trod in their 1814 journey.

D&P - BROTHERS-IN-LAW

E. H. Durfee was the elder of the two partners of Durfee & Peck being 3 years older than C. H. Peck. Each man married one of the Higbie sisters of Penfield, N.Y., making them brothers-in-law.

"COMMANDER" ELIAS HICKS DURFEE

Elias Hicks Durfee was born on December 29, 1828 in Marion, Wayne County, New York, to Elias Durfee (1796-1864) and Mercy Mason (1802-?). The Durfee family had come from Rhode Island, where they had lived since the 1770s. Elias Hicks Durfee (b: 1828) married Lucia Marian Higbie (1832-1906) on Nov. 24, 1852 in Penfield, N.Y. Elias and Lucia Durfee had one child, Charles Higbie Durfee born June 8, 1855 in Marion, N.Y. and died Jan. 28, 1902 in Kansas City, MO.

E. H. Durfee came to Leavenworth, Kansas in 1861 from New York. Durfee's office in Leavenworth was located at No. 48 Main Street in 1867. Durfee was the elder of the two partners; he married the elder sister of the two Higbie girls, and married 4 years before Peck. Fuld suggests that Durfee was the senior partner of Durfee and Peck, and I agree. Elias Hicks Durfee died September 13, 1875 in Leavenworth, Kansas (age 46). Unfortunately I have been unable to find any photograph or painting of Mr. Durfee.

"COLONEL" CAMPBELL KENNEDY PECK

Campbell Kennedy Peck was born on April 8, 1831 to Nathan Peck and Nancy (Kennedy) Peck in Troy, New York. Campbell married Helen Augusta Higbie (1836-1905) of Penfield, N.Y. in 1856, and they had two children: Nellie Peck born on April 24, 1859 and Cady Kennedy Peck born on August 28, 1862 both in Penfield, N.Y. Campbell Kennedy Peck died December 3, 1879 (age 48). Fort Peck was named for C. K. Peck. It was established as a fur trading post by Abel Farwell for Durfee & Peck in 1866-67. From 1873 until 1879 the government used a portion of the fort as the Fort Peck Indian Agency. The site of Ft. Peck was abandoned in 1879, and now is under the waters of Fort Peck Reservoir near Poplar. Unfortunately I have been unable to find any photograph of painting of Mr. Peck.

SCOVILLE MANUFACTURING COMPANY

Fuld states that all the Durfee & Peck tokens, as well as the E. H. Durfee tokens were struck by the Scoville Manf. Company of Waterbury, Connecticut, and those records exist that verify the exact shipping dates and locations.

Fuld notes that his belief is that a diecutter named Ellis (working for Scoville) is believed to have cut the D&P dies, and that a different diecutter name Wumer cut the G. W. Felt dies. From the unusual representation of a buffalo on the D&P token, we could hypothesize that diecutter Ellis not only did not have a photograph of a bison to work from, most likely he had never seen a bison in the flesh. Possibly he was working from period engravings and artwork which he had seen, along with verbal descriptions. The bison depicted on the token appears to have a very long tail!

THE TOKENS' DESIGNS

The idea of having a pictorial representation on the tokens was possibly to enable the Indians who used the tokens, to discern the three different values, since they could (for the most part) not read English. The selection of the subjects of the three pictorials, were scenes that must have been important, and easily recognizable to the Indians. The subjects selected were "the big canoe" (as the Indians called it) or side wheel steamer for the half dollar token, the mounted Indian buffalo hunter for the dollar token, and the running buffalo for the quarter dollar token. The obverse and reverse both have dentiled borders. The wording on the tokens is styled in a beautiful serif font. To add to the beauty, curved lettering spans the center of the tokens. All of the tokens are highly detailed, and beautifully done. The representation of the steamship is quite realistic, but the representation of the buffalo is naive, primitive, and charming.

THE LONG TRIP NORTHWEST FOR THE TOKENS

Fuld states that the D&P tokens were shipped by Scoville in Connecticut to the D&P office at St. Louis, Missouri.

The trip from Waterbury, Connecticut where the tokens were struck, to St. Louis, Missouri, and thence up the Missouri River to Fort Union, Dakota Territory, is a total of about 1,900 miles. I have not found any record of how they were transported from Waterbury to St. Louis; however the typical trips from St. Louis to Dakota Territory are well documented.

The supply trips to Ft. Union were generally made in the spring each year, as the river navigation was closed from November to March. During the spring, the rapid current of the Missouri River was swollen by spring rains, and melting snows, making the waters a swirling mass of snags, logjams, dead trees and debris. This meant that the pilot of the boats going upstream had to be not only extremely vigilant, but it helped if he had years of experience in this type of hazardous navigation. During the year 1834, when German Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and his entourage were making the journey from St. Louis to Ft. Union on the steamship Yellowstone, it took 75 days for the one way trip upstream. A tradition at Ft. Union was to fire a volley as a salute for any approaching or departing boat, with one of the small cannon.

After unloading the supplies for the fort from the steamship, the furs and pelts from the fort were loaded back on the boat. Buffalo robes were packed (at the fort prior to departure) in pressed bales (hide presses were located just outside the palisade). In the year 1834, the steamer Yellowstone on its first trip back downstream to St. Louis carried eight thousand buffalo robes, and about 6,200 wolf and fox hides. The yearly trade for Ft. Union at that time was about 42,000 buffalo robes per year.

THE UPPER MISSOURI RIVER AND PACKET BOATS

Wooden packet boats (a packet boat is generally described as a steam boat for conveying cargo, mail, and passengers on a regular schedule) were the primary means of transit on the Missouri River in 1868. Some of the "keel boats" from earlier years still navigated the river, as well as mackinaw boats, canoes, barges, etc., but most commercial traffic of the traders was done on packet boats. Almost all were run by wood burning steam engines. Some were "side wheelers" and others were "stern wheelers".

By the time Fort Union and Fort Buford were the site of the D&P trading post, two of the steamships making the trip up the Missouri were steamer Benton, and steamer Big Horn. The Benton carried 250 tons of goods in 1868, much of which was furs and pelts from the D&P operation at Ft. Buford. The Benton (which was briefly called Intrepid) was a sternwheeler wooden packet boat. The Benton was launched in 1864, and was snagged and lost in 1869. Most of its life, the Benton was run by Durfee & Peck. On one trip up the Missouri in 1865, the entire pilot house of the ship was sheathed in boiler plate iron, to protect the pilots from Sioux Indian attacks.

1829 -FORT UNION, DAKOTA TERRITORYOld Fort Union, D.T. and Fort Buford, D.T. were located just west of the present day town of Williston, North Dakota, about 30 miles south of the Canadian border. Fort Union was much smaller than Fort Laramie in size. Also, keep in mind, that Fort Union was conceived, built and operated as a totally civilian enterprise, not hampered by, nor aided by federal government rules and military regulations. Ft. Union was built in the autumn of 1829 by the Upper Missouri Outfit (UMO), branch of the American Fur Company (AFC).

Many famous people passed through Ft. Union, including John James Audubon, famous wildlife artist George Catlin in 1832, naturalist German Prince Maximillian, Sioux chief Sitting Bull, mountain men Jim Bridger and Jim Beckwourth.

Fort Union was known as Fort Floyd until about 1830. The physical location is about 100 yards east of the Montana border.

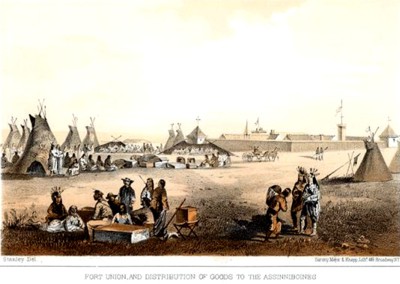

THE PHYSICAL APPEARANCE OF FORT UNION, D.T.

Since we do not have color photographs of Fort Union, here we will attempt to describe the fort's appearance when it was at it's finest (perhaps in the mid1850's). No description of the fort will be entirely accurate, for the fort first built in 1829, rebuilt in 1832, and was being constantly remodeled. Fort Union was built on an elevated meadow on the Missouri River's north bank, about 60 feet from the waters edge. This spot was suggested to the Upper Missouri Outfit, by the Assiniboine Indians. The site was a good one; it was safely above the high water mark of the river. Coulees on the east and west side of the site provided drainage from heavy rains.

French speaking creoles of Missouri (upper Louisiana) mixed with labor and know-how of the French- Canadians, gave the fort have a French colonial appearance.

The plan of the fort was almost square, measuring 245 feet on the north south walls, and 237 feet on the east west walls. The palisade was built in what the Frenchmen called "poteaux-en-terre" or post in the ground. Long trenches several feet deep were dug and large square hewn cottonwood timbers were set on sandstone rocks in the bottom of the trench. Then heavy stones were set around the base of each timber and earth tamped on top of that. The palisade timbers projected 20 feet above the ground. Cross bracing timbers were added on the interior face, after high winds flattened portions of the palisade only one month after completion.

Two story whitewashed stone bastions, or blockhouses, were at the northeast and southwest corners of the fort. Each of these stone bastions had stone walls nearly three feet thick, and thirty foot high, with railed balconies, and sloped shingled roofs painted bright "Turkey red", topped by large American flags. These white and red bastions were visible for miles around the fort. A barracks building for employees was located on the west palisade, and measured 119 feet by 21 feet. It was divided into six apartments for employees. Additional small structures housed hunters, clerks and engagés (contract laborers).

A twenty-one foot by twenty-four foot ice house was west of the bourgeois house, which had a wooden floor and trap door leading down to a basement where the ice was put away each winter.

A stonemason was hired and brought in from St. Louis to construct the required gunpowder magazine. The 25 foot by 18 foot stone powder magazine was constructed of vaulted limestone four feet thick at its base. A wooden shingle roof was built to top the stone vault's ceiling, to deter water damage. In addition the double doors of the magazine were lined with tin. A few of the buildings inside and outside the palisade were constructed of adobe. The stone structures remained after the rest of the fort was deconstructed in 1867, with a bit of adobe.

Entry to the fort was from two pair of huge twelve feet wide by fourteen feet high double gates on the south side which faced the river.

THE RECEPTION ROOM & INDIAN TRADING ROOM

While reading the following description, be mindful that the Durfee & Peck trading post was not within the palisade, but outside the fort walls. This interior trading post was used by the Upper Missouri Outfit (UMO) and later the North West Fur Company (NWFC).

Just inside the double gates of the fort was where the Indian trading took place. Just inside the fort on the west of the main gates was a large house, measuring fifty by twenty-one feet and divided neatly into two pieces. The westernmost side was a combination blacksmith, gunsmith and tinner's shop. Between the blacksmith shop and the gate was the large "reception room" which was for visiting Indians. Since the double gates formed a vestibule after passing through the first set of gates, entry was possible into the "reception room" through this vestibule. This allowed Indians to enter for trade without having access to the main parade ground of the fort. The vestibule size was twelve by thirty-two feet and was closed from the rest of the fort with log pickets.

Just off the reception room, was the "Indian trade room", and the actual exchange of goods took place through a small window in this Indian trade room. This room also was on the exterior of the fort, and had a small window type opening to the exterior of the fort where trading could take place, if the allowing the Indians into the reception area was too dangerous.

THE BOURGEOIS HOUSE AND PARADE GROUND

The head of the fort as called the "bourgeois" (superintendent), and the large house that was the center of the fort or post, was called the bourgeois house. Ft. Union's bourgeois house was near the center of the north wall. The bourgeois house was built in the French-St. Louis poteaux-en-sole (post on sill) construction. It measured about 78 feet by 24 feet in plan, and was a two story weather-boarded structure. The rear wall of the house was about 12 feet from the back palisade of the fort. The house looked as if it had been brought in directly from St. Louis. Painted solid white, each window sported green wooden shutters, it's steeply pitched shingled roof was painted red to preserve the wood. The French called this a pavilion roof. Four dormer windows on the roof allowed light into the attic, balconies were supported by turned wood posts. The entire interior was wall papered and decorated with paintings and prints.

Between the front of the bourgeois house and the fort's front gates was the parade ground, and in the center of the parade ground was the fort's main flag pole. This wasn't just any flagpole either! The pole looked as though it had been stolen from a large sailing ship. It was 63 feet high, and had a crow's nest, and rope trusses supporting the staff on all sides. Upon this large pole the fort flew a huge sixteen by twenty foot American flag, which had once belonged to the U.S. Navy. About the base of the flagpole was twelve foot diameter garden of vegetables, surrounded by an octagonal fence. Near the fence and base of the pole was a small iron four pounder cannon, which was the one fired on special occasions such as the arrival or departure of steamers.

OCCUPANTS OF FORT UNION

The total occupants of the fort most likely never exceeded more that about 100. The occupants had a strict social standing of two classes, the upper class which included the Bourgeois, the clerks, and their families, and the lower classes which generally were the engagés, or contract labor and their families. There was much family life in the fort, much inter-racial marriage, especially between Indian women and the "white men". Of course the "white men" were Caucasoid; there was a large diversity of races represented at the fort, as attested in surviving documents. Hispanics, African-Americans, Canadians, Scotchmen, Germans, Swiss, Frenchmen, Italians, Creoles, Spaniards, Mulattoes and half-Indians are all documented to have lived there. Most of the engagés were male, and most were hired for one or two year contracts to perform various tasks.

The more experienced backwoodsmen, were usually French-Canadians, and called both voyageurs and coureur de bois (woods runner); as opposed to the common laborers hired in St. Louis who were called mangeurs de lard (pork eaters).

FT. UNION'S FOOD

Visiting dignitaries, such as German naturalist Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied, left vivid descriptions of the food served at Ft. Union as early as 1833. Crackers, white bread, fresh vegetables, preserved and fresh fruit, complimented a large selection of meats, including buffalo tongues, venison of elk, deer and antelope. Dairy products were fresh from the fort's milk cows. Chickens, goats and domestic pigs were kept within the fort for food. The absence of coffee, was somewhat eased by availability of iced Madeira and port wines with supper, and pears and cherries were tasty desserts.

THE DISTILLERY AT FT. UNION AND THE WHISKEY PROBLEM

From early times, there had been a problem with the Indians and liquor. Kenneth McKenzie, the bourgeois at Ft. Union in 1833, found a way to circumvent the federal government’s laws on bringing liquor up the Missouri River for the Indians. In the spring of 1833 the steamer Yellowstone made its way up the Missouri with distillery equipment for the trade at Ft. Union. By July of 1833 the still was in full operation, producing moonshine whiskey from Indian corn purchased from the Mandan tribe. Eventually, one of the UMO's competitors "blew the whistle" on McKenzie, and he and Pierre Chouteau, Jr. were compelled to explain this breach of the intent of the anti liquor laws for the Indians. It is completely understandable why this happened, as HBC freely supplied liquor to the Indians with whom they traded, both to grease the wheels of commerce, and to tilt the balance in their favor. The Upper Missouri Outfit was just leveling the playing field. Other Missouri River traders also managed to get whiskey to the Indians, sometimes importing it from the New Mexico area. One famed whiskey man named Simeon Turley at Arroyo Hondo, New Mexico began to manufacture whiskey as early as 1832, and continued well past 1843. Even the famed Santa Fe, New Mexico firm of Bent, St. Vrain & Company (of Bent's Fort, Colorado fame) placed an order with Pratte, Chouteau & Company for six large capacity copper stills. Where these six stills ended up is anyone's guess, as there is no record of a still at Bent's Fort.

UNPLEASANTNESS AT FT. UNION

As with most frontier forts, there was a share of life that was unpleasant. Gonorrhea plagued many of the inhabitants, although rarely recorded in writing; it was a fact of life. Sanitation was a problem, although little written account survives that documents this, it is likely that chamber pots were used at night, and some small latrines were built within the palisade. Horses and livestock were held within the palisade to protect them from theft by the Indians. Plain old animal droppings and human excrement was a problem, and so was the mud and muck resulting from snow, rains combined with the aforementioned waste. This all created a stench within the walls of the fort, and resulted in a "boardwalk" affair criss-crossing the grounds during poor weather. The stench became bothersome during the summer months, when higher temperatures ripened the manure piles. Some of the refuse of the fort's inhabitants was thrown over the walls. Archeologists uncovered one dump outside the north wall of the fort, and another within the walls near the southeast corner.

The strychnine used to kill wolves was sold in one-eighth ounce bottles, which was enough to kill five wolves. Durfee & Peck stated that they had sold as many as 1,200 bottles of strychnine to one trapper!

Fort Union and the surrounding Indian tribes were stricken with an epidemic of smallpox, in June of 1837. During the smallpox epidemic, Charles Larpenteur was the bourgeois and he attempted to inoculate the fort's inhabitants, from reading about this in one of the fort library’s books, "Doctor Thomas' Medical Book". Unfortunately this did not work, as he used live smallpox matter, rather than the required preparation of cowpox, as less virulent strain. The stench of the disease within the compound was so strong that the inhabitants took to carrying vials of camphor pressed to their noses. Within the locked down fort, 27 people became ill with smallpox, four or these died. Larpenteur's own wife's body was covered in maggots and smallpox pustules, for two days of misery before she died. The Indians outside the walls also were inadvertently exposed to smallpox, and it laid waste to their ranks. At least 800 Assiniboine died, 700 Blackfeet, and 800 Arikara Indians succumbed to the disease. The Mandan tribe was virtually wiped out, with only about 30 survivors, and three fourths of the Hidatsa tribes also died.

1864- GENERAL SULLY & BEGINNINGS OF FT. BUFORD

Sioux depredations on steamship traffic had been so intense; the U.S. government sent General Alfred Sully on a campaign against the Sioux, over three summers, from 1863 through 1865. General Sully and his troops arrived at Ft. Union in June of 1864 to guard government supplies meant to build a post near the Yellowstone. Sully studied the decaying wooden fort, and decided that it should be replaced with a new larger government fort, at a site about two and a half miles away at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. This site was to be named Fort Buford.

The U.S. military kept a presence in the area and at Ft. Union for some years. Paroled Confederate prisoners were pressed into military service on the western frontier, and in Oct. of 1864, the 1st Regiment, United States Volunteers arrived at nearby Ft. Rice, with 23 year old Colonel Charles Dimon in command. After spending a miserable winter at Ft. Rice, the volunteers were distributed at other forts up and down the Missouri, including about 50 men of Company B which were billeted at Ft. Union. Colonel Dimon is of interest, because he was somewhat paranoid, and seemed to find apparent insurrection and insubordination everywhere. He even had one of his soldiers shot for a muttered remark. In February of 1865, Col. Dimon suspended the regularly licensed Indian trader’s privileges, and put the Indian trading in the hands of the post sutler at the fort. This shows the sometimes blurred line between post sutlers and Indian traders that did occur on occasion.

1866-FT. UNION SOLD TO NORTHWEST FUR COMPANY

"American Fur Company" sold Fort Union to the "Northwest Fur Company" (not the "North West Company") in 1866, and was in their hands for about one year.

1867-LOCATION of the DURFEE & PECK TRADING POST STORE at FT. UNION, D.T.

By the time the Durfee & Peck trading post was established at Ft. Union, the days of glory for old Fort Union were long since past. More furs were being shipped from further west; gold had been discovered further west in Idaho and Montana. Fort Benton had become the new hub of the fur trade. Scores of steamers traveled the Missouri.

In June of 1867 ex-Ft. Union bourgeois Charles Larpenteur returned to Fort Union on board steamship Jeannie, as a trader representing the firm of Durfee and Peck. He and his men built a trading post just outside of the log palisade fort which was the fur trading business of the North West Fur Company.

The Durfee & Peck store was under construction during the month of June of 1867, the construction being supervised by Larpenteur. The 96 foot by 20 foot D&P store was constructed of adobe brick just outside of the palisade, and west of the fort. The D&P adobe trading post also had a bastion, and some out-buildings, including a kitchen. The adobe D&P store opened for business on July 1, 1867 at Ft. Union. It remained in business only about 40 days before the move to Ft. Buford began.

Larpenteur noted that on August the 7th 1867, the soldiers began to tear down the recently purchased Fort Union. Larpenteur started to move all the Durfee & Peck stock of trading goods, furs, hides and furnishings from the Ft. Union adobe buildings, to the new building at Ft. Buford on August 10th, 1867. The "new" D&P store at Ft. Buford was still not complete, from late October until November 1867. Larpenteur and his engagés were busy hauling sawn lumber, goods, timber and pelts to the new location at Buford. The Buford store, being 120 feet long, was complete by November 25th, 1867.

The North West Fur Co. maintained clerks at their Ft. Union trading post until September 26th, 1867, when they also moved to Fort Buford.

Durfee & Peck were in competition not only with the owners of Ft. Union (North West Fur Company), but another Indian trader group: Gregory, Bruguier and Geowey (GBG) who had two small rude wooden buildings east of the main fort structure. This made a total of three different fur and hide trading companies represented at this one location during the summer of 1867, GBG one the east, D&P on the west and North West Fur Company operating the main fort.

During the summer of 1867 the Ft. Union location of D&P under Larpenteur did a great business, even with the mayhem of new construction and moving from Union to Buford in August. They acquired two thousand buffalo robes, 900 elk hides, 1,800 deer skins, and 1,000 wolf skins. This rosy picture did not last long, as the management of D&P fired Larpenteur when they arrived by steamboat on May 18, 1868.

FORT BUFORD, DAKOTA TERRITORY

By the start of the Civil War in the early 1860s, Ft. Union was 30 years old, and General Alfred Sully described Ft. Union as "an old dilapidated affair, almost falling to pieces." So the Army decided a new larger fort should be established, close to Ft. Union, but at a better site, considering flooding, water wells, defensibility and accessibility from the river. General Sully arrived at Ft. Union with Company I, 30th Wisconsin Infantry which were garrisoned there to guard the fort, and supplies.

Ft. Buford, D.T. was established on June 15, 1866. It was located on the north bank of the Missouri River, just below the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. Ft. Buford was about 2 1/2 miles from the earlier Fort Union. The post was intended to protect the emigrant route from Minnesota to Montana, and guard the commercial navigation along the Missouri River. Fort Buford was conceived, built and operated as a military fort for the U.S. Army. It is possible that Durfee and Peck held a "post trader" license at Ft. Burford, as it is verified that D&P did in fact hold military post trader licenses at some locations (unverified by me which locations).

Fort Buford was named for Major General John Buford (of Gettysburg fame) who died December 16, 1863. Ft. Buford was established by Brevet Lieutenant Colonel William G. Rankin commander of Company C, 13th U.S. Infantry (the 13th Infantry became the 22nd Infantry in the reorganization of 1867), on a site selected by Major General Alfred H. Terry. Fort Buford had outlived its main purpose by the 1890s, and was abandoned on October 1, 1895. The garrison was transferred to Fort Assiniboine, Montana. A small contingent of troops remained at the site as it was closed down until November 7, 1895. The site was transferred to the Department of the Interior on October 31, 1895.

Ft. Buford was planned as a rectangle, 333 yards by 200 yards, surrounded by a 12 foot high wooden stockade on three sides. The side facing the river was not stockaded. The barracks buildings were of adobe brick, the remaining buildings were made from cottonwood. I was unable to determine the cutoff date of the Durfee & Peck store at Ft. Buford, however the fort itself was abandoned in 1895. Since Mr. Durfee died in 1875, I would say the approximate date for use for the tokens at Ft. Buford was from 1867 thru 1875.

THE ADVANTAGE OF THE LOCATION FOR BUFFALO TRADE

The big advantage of the location of Ft. Union, D.T. as a receiving point for buffalo hides in 1868, was that it was smack on the Missouri River, and indeed at near the headwaters of that river. Therefore, any bison robes received at this point, could simply be loaded on one of the steam packet boats, and head downriver, to the markets in St. Louis. In this regard, Durfee and Peck had a big advantage over most of the trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company, who had to ship any hides or pelts overland to their York factory.

THE VALUE OF 25 CENTS in 1868

The Durfee & Peck tokens were issued in 25 cent, 50 cent and $1.00 denominations. Adjusting for inflation, the 25 cents of 1868 would be worth about $4.48 in today’s goods. Multiply that by two and four and you have the other two tokens adjusted worth in goods.

DAKOTA TERRITORY IN 1868- TEMPERATURES-GEOGRAPHY-HISTORY

At first Dakota Territory was comprised of South Dakota, North Dakota along with parts of Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. In 1868, Montana and Wyoming each became separate territories. Average temperature during a year at the site of Fort Union is 37 degrees F. The coldest month is January with average temperature of 2 degrees; warmest is July with average temperature of 67 degrees F. Average snowfall per year at the Fort Union site is 31 inches; average total precipitation per year is about 16 inches.

INDIAN TRIBES OF THE AREA

Fort Union, Dakota Territory was built specifically to serve the Assiniboine (pronounced Uh-sin-uh-boin) tribe. The Assiniboine tribe was the most important tribe of the upper Missouri River. The fort was built on their land. There were 9 main tribes in the area of Fort Union. I have prepared a chart, indicating the tribes in order of most to least important:

|

Tribe name |

Language |

Also Known as |

Type existence |

|

Assiniboine |

Sioux related |

------ |

nomadic hunters |

|

Crow |

Sioux related |

Hidatsa |

nomadic riverine |

|

Blackfoot |

Algonkian |

Piegan, Blood, Blackfoot, small Sarsi |

nomadic hunter-gatherers |

|

Plains Cree |

Algonkian |

Cree |

plains culture, tipi dwelling & buffalo hunting |

|

Plains Chippewa |

Algonkian |

Ojibwa, Chippewa |

plains culture, tipi dwelling & buffalo hunting |

|

Mandan |

Sioux related |

friends of Lewis & Clark expedition |

earthlodge dwelling, agricultural, and hunting, fur traders |

|

Hidatsa |

Sioux related |

group from which Crow split |

similar to Mandan |

|

Arkira |

Caddoan |

splinter group from Pawnee |

riverine, semi-sedentary |

|

Sioux |

Sioux |

Dakota, Nakota, Lakota, Ogalala, Brule, etc. |

nomadic hunters and gatherers, plains culture, tipi dwelling |

The Indian tribes in the area were devastated by a smallpox epidemic in 1837, up to 90% of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes were killed by the epidemic. Inoculation were attempted, but proved unsuccessful.

THE REASON for SEPARATE D&P TOKENS and E.H. DURFEE TOKENS

Below you will read that E. H. Durfee by himself controlled the "southern trade" with the Plains Indian tribes, while a different business venture partnered him with Mr. Peck to trade with the "northern trade."

The following quote is taken from the May 8, 1868 "Leavenworth Daily Conservative" newspaper, concerning the firm of Durfee & Peck, and the buffalo hide trade:

Probably there is no business carried on in this country of which so little is known by the public generally as Indian trading. We yesterday had a very interesting chat with Mr. E. H. Durfee, one of the oldest and most widely known Indian traders who have ever been about the business, which we have decided to lay before our readers.THE SOUTHERN TRADE

He is the sole proprietor of the establishment here, which is the headquarters for the traffic with the Southern Indians. The posts on the upper Missouri are owned by Durfee & Peck. The Southern Indians, or those south of the Arkansas, supplied, are the following, with their estimated numbers: Comanches, 23,600; Apaches and Cheyennes, 3,500; Osages and Kaws, 4,000. The larger tribes, as nearly everybody knows, are divided into bands, under various names, which we will not give here.

THE NORTHERN TRADE

The Indians of the North with which they trade are all Sioux, numbering, it is estimated, upwards of 70,000. They are located in Dacotah (sic) and Montana. The Sioux are divided into twelve or fifteen bands. Some of their trade comes from the British Possessions, and the whole extent of it is from there to Texas. The only rival of Durfee & Peck is the Northwestern Fur Company. The competition is sharp, and is carried on with all the energy which characterizes the Yankee everywhere in Wall street or in a log cabin a thousand miles from civilization.

THE POSTS, AND MEN EMPLOYED

Durfee & Peck have employed at their posts, in all, about one hundred men. A large number of these are fitted out every season by them with arms and traps with which they get their furs and turn them over to their employers, receiving therefore goods, which they in turn sell to the Indians.

They have on the upper Missouri seven posts, at which are stored and kept for sale all kinds of goods which the Indians want to buy, and where they come in with their skins. The houses used are all built of logs, with mud roofs, saw mills being scarce up that way.

THE HUNTING AND TRAPPING SEASON

The season in which furs and peltries are secured by the hunters and trappers is from October to February. After that time the shedding of the coat commences and the hair fades and becomes worthless. The animals most sought for and which produce the most desirable skins are the following, placed in the order of value: Otter, beaver, buffalo, wolf, elk, bear, fox, deer, and coon. Mink is considered too small game, among the Indian trappers in particular.

HOW THEY ARE KILLED

The buffalo are killed mostly with arrows, as they are not only less expensive, but can be withdrawn and used again. These animals are generally hunted in the following manner: A large herd is surrounded and gradually driven in together. And there is exhibited a piece of strategy thoroughly Indian. The stragglers on the outside of the main herd are shot in the liver and will bleed to death internally in going four or five miles. The hunters will keep on driving them, and the carcasses at the close of the chase are not scattered over so large an extent of ground as they would be if the stragglers were shot dead. When the circle is well closed in, the hunters begin to shoot at the heart. Their ponies are all trained and will not enter the herd, but keep always around the outside, though the rider does not draw a rein on them after the main herd is reached.

The wolves are all poisoned in the following manner: A quarter of buffalo is either taken in a wagon or dragged over the prairie; at the distance of about 40 rods apart, numerous stakes are stuck in the ground, on the top of which is impaled a small piece of the meat, which has been poisoned with strychnine. The wolves strike the trail and follow it up, taking the pieces as they go. Next morning the hunters go along the line and skin the dead animals.

DRESSING AND TANNING

The Indians use the brains of the animal to tan it with. They first stretch the skin over a frame. They then rub on the brains, mixed with juices obtained from certain roots and plants. They are then scraped with various implements, hoes being used. They say the brains draw out the grease. After they are dry, they are painted and ornamented. The paint used is of the very finest qualities of Chinese vermillion and chrome yellow and green. These are imported by Durfee & Peck.

BRINGING IN THE SKINS

As soon as the season is over the Indians put the hides and furs on poles, which are dragged by ponies, sometimes a distance of 300 miles, to the nearest trading post. The whole band generally comes in with them. At the posts are opposition runners, in the employ of the Northwestern Company and Durfee & Peck. They keep on the watch, and as soon as a band comes in sight they mount their ponies and start off to secure the customers. Those with whom they decide to trade are compelled by custom to give the band a great feast, which lasts one day. Then business commences.

WHAT THE INDIANS BUY

The articles most in demand by the red men are coffee and sugar, of which they are very fond. In dry goods they want blankets, cloth, prints; a few of them buy saddles and bridles. An ornament called an Iroquois shell, which is picked up on the seashore somewhere in Europe, is in great demand. Mr. Durfee says he has seen an Indian sell fifteen out of twenty buffalo robes for these shells.

BIG CANOES

The Indians know the boats which are loaded with goods for them by the tops of the smokestacks being painted red. They call them "big canoes," and as soon as they get into Indian country the news is carried ahead by runners, and they all know when the boat will arrive. They ever molest them, and Durfee & Peck have never met with any loss at their hands.

MISCELLANEOUS

Mr. Durfee has sent off one boat load of goods this season, per steamer Benton, which will be back in June, loaded with furs, robes and peltries. She took up 250 tons. The Big Horn, which has gone up with Government freight, will also bring down a cargo. The Benton will also make another trip this season. The farthest that the boats go up from Leavenworth is 2,700 miles, by the river. The proceeds of the stock to be brought down by the Benton this year will be about $150,000. They have sutlers stores at Forts Sully, Rice and Stevenson, which are entirely separate from the Indian business.

Durfee & Peck handle yearly from 25,000 to 30,000 buffalo robes, which average about $8.00 apiece. The furs are, of course, much higher, and the whole business comprises an enormous trade. There is a popular idea that some of the buffalo robes which we find in market are tanned by white men. This is not so. The Indians do it all. White men have tried it, but failed.

Mr. Durfee has, during his various trips to the mountains secured a large number of pets; among them he has kept the following animals, which are at his New York residence: one bear, one antelope, one deer, one badger, a red fox and two American eagles. He had two buffalo but they died.

A separate 1871 article is also quoted here, because of the dramatic and unique language used in the description of the trade business:

DURFEE & PECK.

The commercial cities of Europe long strove for the East India trade, but to Leavenworth is assigned the honor of ascendancy in dealings with the Red man. The extent of Messrs. Durfee & Peck's business in the Upper Missouri region, where the warlike Sioux wage unceasing warfare with the buffalo and other savage prey; and in the Indian Territory, where the influence of civilized neighbors is not sufficiently strong to restrain the nomadic aborigine from treading in the footprint of his fore-fathers, is already known to our readers. Every summer the spoils of these primitive Nimrods are gathered by the daring employees of this firm at their various posts in the Upper Missouri waters, and dispatched to business headquarters in this city. These shipments continued during the season, result in an accumulation of hides and peltries in their warehouse which may be numbered by thousands. In the fall these furry spoils are carefully assorted and baled, and shipped to New York for sale. Notwithstanding the constant encroachment of the white man upon the immemorial hunting grounds of the Indian, and the threatened extermination of the buffalo, we are informed by Mr. Durfee that no diminution in his business is yet apparent. Another important branch of the business of this house is the keeping of sutler posts at the many military stations on our western frontier, by order of the Secretary of War. This renders them large purchasers of liquors, groceries, dry goods, cutlery, etc., and it is greatly to the credit of Mr. Durfee that whenever he can make his purchases of the merchants and manufacturers of this city, he invariably gives them the preference. We mentioned in our notice of the Eagle Woolen Mills, that establishment were running off cloths for Durfee & Peck's Indian trade. In addition to these important branches, this enterprising house is also an extensive owner of the Northwestern Transportation Company's stock, and several of the finest vessels that stem the turbid waters of the Upper Missouri were built by this house. We may mention that this firm is deservedly popular throughout the West, as fairness and liberality characterize all their dealings. The location of their headquarters in this city is also a great advantage to Leavenworth, as their business affords employment for many men, and their disbursements among our merchants are quite liberal.

(From the Dec. 31, 1871 Leavenworth Kansas "Daily Commercial" newspaper)

WHY THE DIFFERENT METALS?

Why were the D&P tokens issued in copper, brass, copper-nickel and white metal? We can only guess what the reasons might have been for ordering and striking the tokens in at least four metals. My first thought was that they had only been struck in the various metals at the Scoville Manufacturing plant, as die trials, to see how the dies would look in various metals. However, Fuld states plainly that Durfee indeed ordered the 25 cent token in four metals in 1869. Therefore, we must assume there was some business purpose for having the same denomination in several metals. One hypothesis is that each year, a switch in metals, might make for a crude form of bookkeeping, allowing the traders to see when the tokens issued, were actually spent. Another thought is that a different metal token, might be used at each of the trading posts or sutler operations that D&P operated, again a crude form of bookkeeping.

DURFEE & PECK -LOCATIONS OF TRADING POSTS & SUTLER STORES

Known D&P stores:

1. Fort Sully, D.T. - sutler 1868

2. Fort Stevenson, D.T. - sutler 1868

3. Ft. Union, D.T. - Indian Trader -1867

4. Ft. Buford, D.T. - Indian Trader -1867-?

Known E. H. Durfee locations:

1. The mouth of the Arkansas River

2. Current location of Wichita, KS

3. Various locations as Indian trader with Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches 1866

OTHER KNOWN DAKOTA TERRITORY INDIAN TRADER & POST TRADER TOKENS

Some of the other known tokens of Dakota Indian and post traders are these:

1. J. S. McCormick, Post Trader, Ft. Laramie, D.T. (Curto F84)

2. John London, Post Trader, Ft. Laramie, D.T. (Curto F85, F86, F87)

3. J. Wanless, Retail Dealers (shell card) Fort Sanders, D.T. 1868 (Curto F169)

4. W. S. Fanshawe & Co., Post Traders, Ft. Meade, D.T. (Curto PT3)

5. F. J. D. & Co., Ft. Thompson, D.T. (Curto F195, F196, F197)

EPILOGUE

In 1966 the U.S. Congress designated the site of old Fort Union, Dakota Territory, near current day Williston, N.D., a unit of the National Park Service. Archeological excavations, and historical records of the fort, allowed for an accurate reconstruction of the fort, which was almost complete by 1995. Currently the fort is pretty much complete; the bourgeois' house is a very authentic reconstruction of the original. Reinactors stage various recreated events for tourists dressed in 1870s military uniforms at Ft. Union.

Major References: Fort Union and the Upper Missouri Fur Trade by Barton H. Barbour, 2002; Token Collector's Pages by George and Melvin Fuld, 1972; Fort Buford and the Military Frontier on the Northern Plains by Utley, Rickey & Warner, 1987; Peddlers and Post Traders, by David M. Delo.

Minor References: Forts of the Upper Missouri by Robert Athearn, 1967; The Buffalo Book by David Dary, 1989; Selected Articles on the Subject of American Tokens Reprinted from "The Numismatist" by TAMS, 1969; American Business Tokens by Benjamin P. Wright, 1972; Indian and Post Trader Tokens-Our Frontier Coinage by J. J. Curto, undated; Military & Trading Posts of Montana by Miller and Cohen, 1978.

Back to page 1 of token web pages...

updated 12 feb 2004